Overview

A memory consistency model for a shared address space specifies constraints on the order in which memory operations must appear to be performed (to become visible to the CPU) with respect to one another

This includes operations to the same locations or to different locations and by the same process or different processes. In this sense, memory consistency subsumes coherence

Hardware Memory Models

A hardware memory model specifies hardware guarantees for a programmer writing assembly code. The assumption is that each thread is executing on its own dedicated CPU and that there’s no compiler to reorder what happens in the thread

Sequential Consistency (SC)

A multiprocessor is sequentially consistent if the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the CPUs were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual CPU occur in this sequence in the program order

Every process appears to issue and complete memory operations one at a time and atomically in program order. It should appear globally as if one operation in the consistent interleaved order executes and completes before the next one begins

Two constraints:

- Program order - Memory operations of a process must appear to become visible (to itself and others) in program order

- Write atomicity - All writes (to any location) are seen in the same order by all CPUs

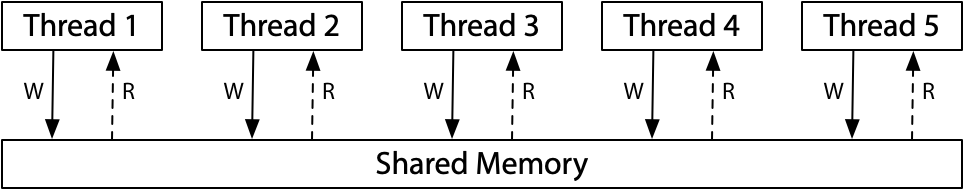

A good mental model for sequential consistency is to imagine all the CPUs connected directly to the same shared memory, which can serve a read or write request from one thread at a time. There are no caches involved, so every time a CPU needs to read from or write to memory, that request goes to the shared memory. The single-use-at-a-time shared memory imposes a sequential order on the execution of all the memory accesses: sequential consistency

Giving up strict sequential consistency can let hardware execute programs faster, so all modern hardware uses weaker memory models

Synchronization

We still may need synchronization because SC works at the granularity of individual instructions

Synchronization is needed if we want to preserve atomicity (mutual exclusion) across multiple memory operations from a process or if we want to enforce constraints on the interleaving across processes

Total Store Order (x86-TSO)

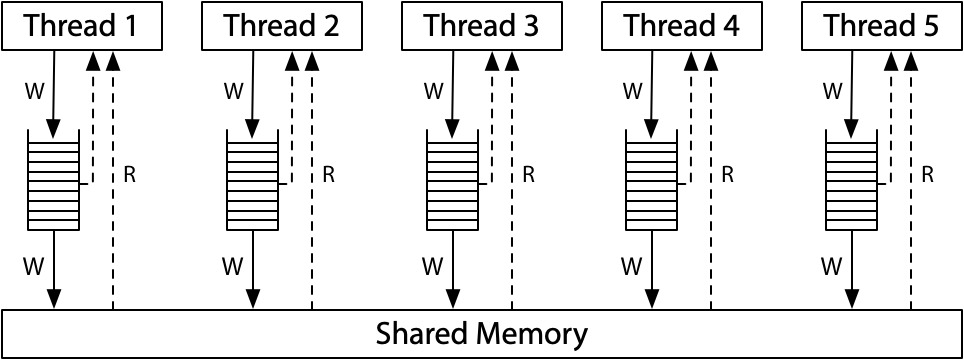

All the CPUs are still connected to a single shared memory, but each CPU queues writes to the memory in a local write queue. The CPU continues executing new instructions while the writes make their way out to the shared memory. A memory read on one CPU consults the local write queue before consulting main memory, but it cannot see the write queues on other CPUs. The effect is that a CPU sees its own writes before others do

All the CPUs agree on the total order in which writes reach the shared memory. At the moment that a write reaches shared memory, any future read on any CPU will see it and use that value (until it is overwritten by a later write, or perhaps by a buffered write from another CPU)

The write queue is a FIFO queue: the memory writes are applied to the shared memory in the same order that they were executed by the CPU (program order)

ARM Relaxed Memory Model

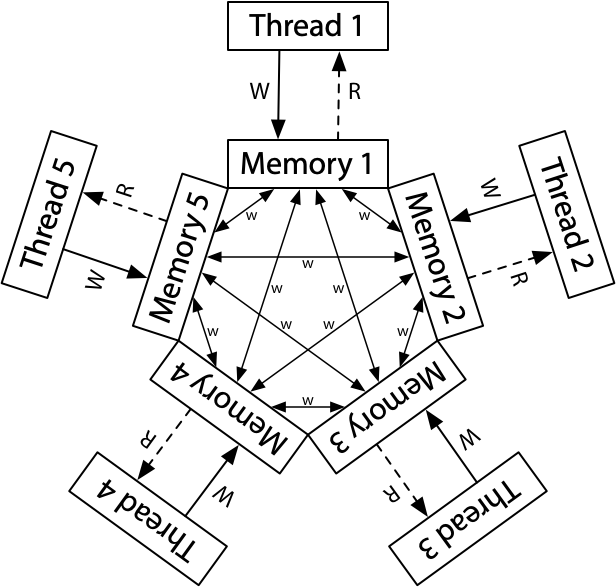

The conceptual model is that each CPU reads from and writes to its own complete copy of memory, and each write propagates to the other processors independently, with reordering allowed as the writes propagate

There is no total store order. Each CPU is also allowed to postpone a read until it needs the result: a read can be delayed until after a later write

But there is a total order for the writes to a single memory location. That is, CPUs must agree which writes overwrite other writes, the property called coherence which all hardware guarantees

Weak Ordering and Data-Race-Free Sequential Consistency (DRF-SC)

A synchronization model is a set of constraints on memory accesses that specify how and when synchronization needs to be done

Hardware is weakly ordered with respect to a synchronization model if and only if it appears sequentially consistent to all software that obey the synchronization model. Weak ordering is “a contract between software and hardware,” specifically that if software avoids data races, then hardware acts as if it is sequentially consistent

Data-race-free (DRF) synchronization model assumes that hardware has memory synchronization instructions separate from ordinary memory reads and writes. Ordinary memory reads and writes may be reordered between synchronization instructions, but they may not be moved across them. That is, the synchronization instructions also serve as barriers to reordering

A program is data-race-free if, for all idealized sequentially consistent executions, any two ordinary memory accesses to the same location from different threads are either both reads or else separated by synchronization operations forcing one to happen before the other

A memory consistency model supports “SC for DRF programs” (DRF-SC) if all executions of all DRF programs are SC executions. That is, a system guarantees to data-race-free programs the appearance of sequential consistency

Modern CPUs provide DRF-SC instead of SC, by defining synchronizing instructions, which provide a way to coordinate different CPUs

Programming Language Memory Models

A programming language memory model specifies the behavior parallel program can rely on to share memory between their threads. It specifies allowed compiler optimizations like register usage and operations reordering

All modern programming languages converge on DRF-SC adopted from the hardware memory model. That is, DRF programs always execute in a sequentially consistent way, as if the operations from the different threads were interleaved, arbitrarily but without reordering, onto a single CPU

Languages provide special functionality, in the form of sequentially consistent synchronizing atomics ofthen called just atomics or atomic operations, to allow a program to synchronize its threads. Programs use synchronizing instructions provided by DRF-SC hardware to establish happens before relationship between code running on different CPUs

Atomics allow simultaneous reads and writes which behave as if run sequentially in some order: what would be a race on ordinary variables is not a race when using atomics. But it’s even more important that the atomics synchronize the rest of the program, providing a way to eliminate races on the non-atomic data

All major hardware platforms implement efficient sequentially consistent synchronizing atomics

Example

Consider this program in a C-like language, where both x and done start out zeroed

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1; while(done == 0) { /* loop */ }

done = 1; print(x);Although each language differs in the details, a few general answers are true of essentially all modern languages:

- If

xanddoneare ordinary variables, then thread 2’s loop may never stop. A common compiler optimization is to load a variable into a register at its first use and then reuse that register for future accesses to the variable, for as long as possible. If thread 2 copiesdoneinto a register before thread 1 executes, it may keep using that register for the entire loop, never noticing that thread 1 later modifiesdone - Even if thread 2’s loop does stop, having observed

done == 1, it may still print thatxis 0. Compilers often reorder program reads and writes based on optimization heuristics or even just the way hash tables or other intermediate data structures end up being traversed while generating code. The compiled code for thread 1 may end up writing toxafterdoneinstead ofbefore, or the compiled code for thread 2 may end up readingxbefore the loop

To fix this issues we should use atomics. Making done atomic has many effects:

- The compiled code for thread 1 must make sure that the write to

xcompletes and is visible to other threads before the write todonebecomes visible - The compiled code for thread 2 must (re)read

doneon every iteration of the loop - The compiled code for thread 2 must read from

xafter the reads fromdone - The compiled code must do whatever is necessary to disable hardware optimizations that might reintroduce any of those problems

In the original program, after the compiler’s code reordering, thread 1 could be writing x at the same moment that thread 2 was reading it. This is a data race. In the revised program, the atomic variable done serves to synchronize access to x: it is now impossible for thread 1 to be writing x at the same moment that thread 2 is reading it. The program is data-race-free.

References

- Computer Organization and Design RISC-V Edition The Hardware Software Interface (2nd ed). David A. Patterson, John L. Hennessy

- Software Approach (1st ed). David Culler, Jaswinder Pal Singh, Anoop Gupta

- volatile (computer programming) - Wikipedia

- research!rsc: Memory Models

- cis.upenn.edu/~devietti/classes/cis601-spring2016/relaxed-consistency.pdf